Writing is thinking. What about co-writing with AI?

Reflections on the blank page in the Age of AI

Our fourth episode of Raising Kids in the Age of AI delves into a question that’s at the heart of conversations about AI and learning: Is it ok to use AI to help with writing?

This has been an obsession of mine from the moment I first got my hands on GPT-3 back in 2021, and I have a lot to say about it. Far more than would fit into a 23-minute podcast episode.

If you’re looking for an accessible discussion with some practical suggestions for parents, check out the episode on YouTube, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts!

For everyone else… it was the French philosopher Blaise Pascal who wrote, “I would have written a shorter letter, but I did not have the time.”

In this piece, I’ll start at the foundations of the question, exploring whether there is some intrinsic, essential metacognitive value in the literal act of writing that cannot be replaced by AI. After establishing a positive statement about the importance of writing, I’ll step back and address the normative dimension: should we encourage the use of AI to write, and if so, how?

We all have our own Thucydides

Shortly after ChatGPT was released, the NYT best-selling author Robert Greene was asked for his opinion on AI. Here’s what he said:

“I don’t like AI,” he said. “I’m thinking back to the moment when I was 19 years old and I was at Berkeley. And I remember, they gave us a passage of Thucydides, the hardest writer of all to read in ancient Greek. So I had this one paragraph, and I must have spent 10 hours trying to translate that one paragraph. Finally, I get to what I think is the answer. I turned it in to my professor, and he goes, ‘Robert, you were almost there, but you missed it. You completely mistranslated this beautiful paragraph, but you were getting at something. That had an incredible impact on me, even to this day. It developed character. It developed patience. You’ve got kids nowadays who are never going to have that experience.”

Long before most people were talking about the implications of LLMs on learning and cognition, Greene intuited something that is now at the center of conversations about AI and the future of education.

I never read Thucydides, but as a Political Science major at Ohio State most of my classes were graded based entirely on just two in-person essay exams. One midterm and one final. Thanks to a mixture of undiagnosed ADHD and procrastination, I regularly found myself desperately cramming the night before.

One memory stands out from PS835, Game Theory and Political Analysis. I had signed up because it sounded “cool,” only to find myself in one of the most notoriously difficult courses in the department. It was the night before the midterm, and I was making slower headway than expected through the readings (who knew a polisci class could have so much math??). I checked my watch—it was almost 3am. The exam was at 8:30, and it would take me about 30 minutes to walk there. I frantically flipped through the course syllabus to see how much I had left to read… more than 400 pages. I had 5 hours to get through the equivalent of an average novel, and hadn’t even begun to drafting my outlines.

Panicking, I indulged in some futile back-of-the-napkin calculations to see if I could pass the class if I failed the midterm. At this point, it was too late to change classes, and so there was a decent chance I wouldn’t be able to graduate on time. No dice.

I allowed myself some time to ugly cry and wallow in the despair of my (admittedly self-inflicted) situation, take a cold shower, and create a 5-hour playlist with all of my favorite Enya albums. And I got to work.

I didn’t ace the midterm, but I didn’t fail. I don’t remember my grade, and for that matter, I also don’t remember much about the game theory of nonproliferation. What I can tell you is that this was a formative experience that always comes to mind when I reflect on the value of my college degree.

I honed durable skills like grit and perseverance. But I also developed the ability to quickly digest, synthesize, and communicate about complex topics. Suffice it to say this has served me well when doing my best to keep up with the pace of AI.

That’s one of my stories about the importance of productive struggle in my education. You have your own.

Like Robert Greene, I worry about the implications of kids never having the experience of sitting in front of a blank piece of paper, pushing through writer’s block, struggling to articulate a complicated idea.

“Desirable difficulties”

Psychologists have a term for what Greene and I are describing: “desirable difficulties.” UCLA researchers Drs. Robert A. and Elizabeth L. Bjork coined the phrase in a landmark 2020 paper that is widely considered to be foundational to the modern science of learning. Its core findings have been validated by thousands of studies over the past decades.

The central idea of “desirable difficulties” is that learning strategies which feel difficult and slow down performance in the short term often lead to superior long-term retention and understanding. Bjork’s research explains why rereading a chapter feels smooth and reassuring, but much of that comfort comes from familiarity, not understanding. Forcing yourself to retrieve the ideas from memory without looking, or to explain them in your own words, are the types of behaviors that make the learning stick.

In study after study, learners who have to generate a solution, a definition, or a summary retain the material better and transfer it more flexibly than those who simply review polished examples. From the outside, those struggling through the learning process look like they’re doing worse, but weeks or months later, they demonstrate better recall and ability to apply the learning.

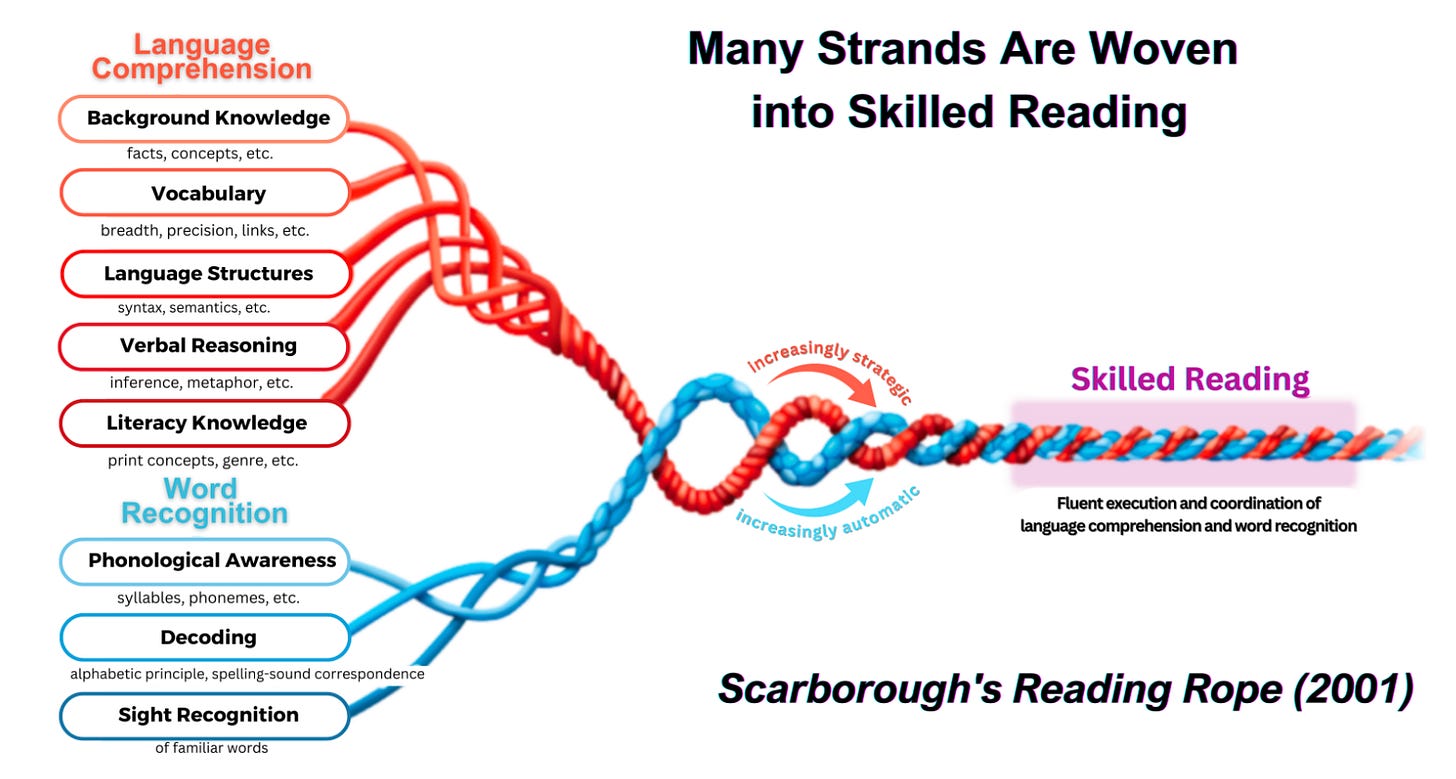

“Desirable difficulties” underpins the so-called “Science of Reading” movement, which insists that real literacy is built by letting kids grapple with text the way real readers do. Educators will recall Dr. Hollis Scarborough’s Reading Rope, which visualizes how skilled reading requires weaving together two main bundles of skills: word recognition (like phonics) and language comprehension (like vocabulary and background knowledge).

The Science of Reading calls for giving students decodable texts that actually force them to sound out words, spacing and revisiting key patterns over time, and regularly asking them to retrieve what they’ve learned instead of just re-reading or guessing from pictures.

When we ask students to summarize a passage in their own words, respond to a prompt in a reading journal, or plan and draft an argument about what they’ve read, we’re layering an additional desirable difficulty on top of decoding: now they have to organize ideas, monitor whether they make sense, and revise when they don’t.

Greene’s struggle to translate Thucydides and my all-nighter weren’t important just because they developed persistence and grit; the struggle itself is at the heart of learning and intellectual growth.

That’s because writing is thinking.

Writing is Thinking

In 2002, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough sat down for an interview with Humanities Magazine where he said:

“You can’t learn to play the piano without playing the piano, you can’t learn to write without writing, and, in many ways, you can’t learn to think without thinking. Writing is thinking. To write well is to think clearly. That’s why it’s so hard.”

“Writing is thinking” is more than a clever aphorism; McCullough was eloquently conveying an idea that has, like Bjork’s research on “desirable difficulties,” been the subject of hundreds (probably thousands) of studies spanning neuroscience, anthropology, media studies, literary theory, and the learning sciences.

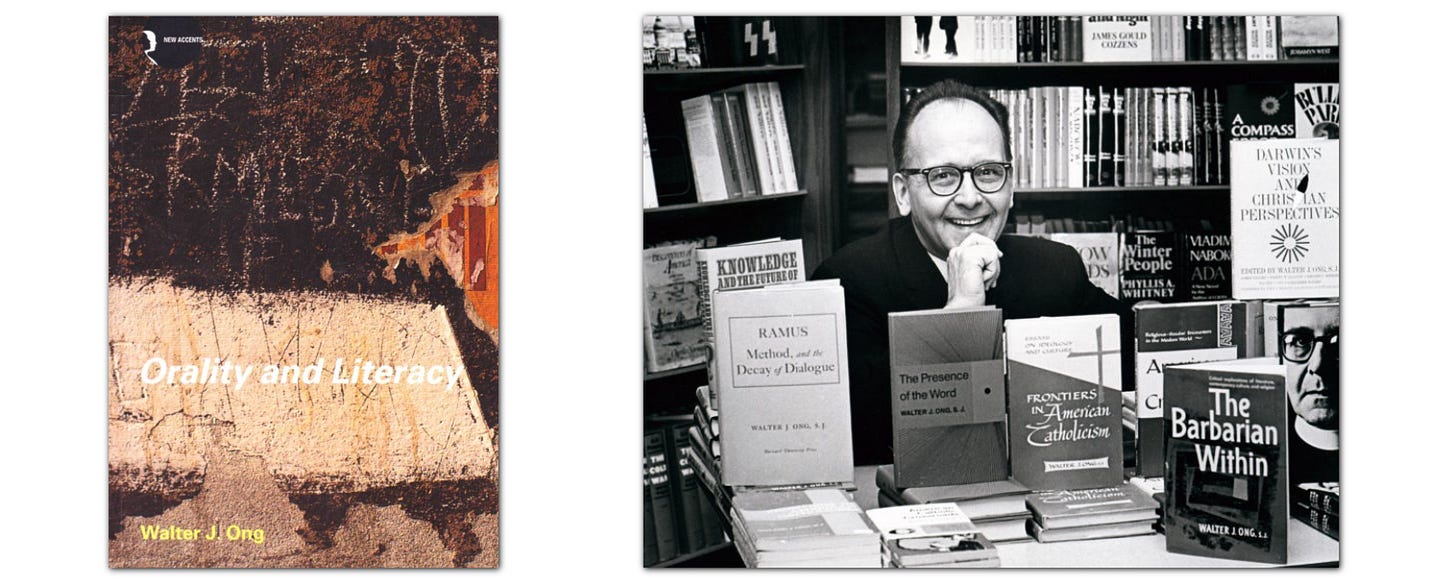

The most provocative and foundational case for “writing is thinking” comes from the media theorist and scholar Walter Ong, whose seminal 1982 book, “Orality and Literacy,” argues that writing is not just a passive tool for recording pre-existing thoughts. Rather, writing is a technology that “restructures human consciousness.”

Without writing, Ong says, ideas are fleeting, momentary events. They float in and out of your consciousness, perhaps from the subconscious, but without a way to write them down, they are elusive. Writing changed everything because it “technologizes the word.” When you write a thought down, you “freeze” it in time and space. That fleeting, subconscious intuition is suddenly a static, visual object on a page. Writing allows you to separate the thought from the act of thinking it.

Writing establishes structure in that it demands logic. You can’t just speak. You have to use punctuation, create sentences, etc. Ong says the technology of writing forces you to build a logical structure for your thoughts, one that might not have existed before you started writing.

Essentially, writing directly enables metacognition.

It’s a powerful argument. It’s also important to mention that Ong’s work is rightly criticized for being overly focused on what he called a “Great Divide” theory about literate societies being superior to oral ones. It’s a problematic oversimplification that implies a linear progression from what Ong calls “primitive” oral thought to “advanced” literate logic, and reflects a colonialist view that ignores the hidden complexity of oral societies.

The wayfinding techniques of Polynesian navigators are a prime example of this: Polynesian peoples managed to traverse unimaginable distances in relatively basic watercraft without modern navigation technologies.

Anthropologists theorize that these navigators held in their minds a massive, multivariable calculus of star charts, wave patterns (how waves refract off distant, unseen islands), bird flight paths, wind shifts, and currents. This is unquestionably higher-order scientific and analytical reasoning, all stored and transmitted orally.

But we do not live in an oral society today. I can barely navigate San Francisco, where I have lived for 10 years, without resorting to GPS.

Ong’s faulty worldview is a caveat that must be called out, but it doesn’t refute the importance of writing. After all, writing is the predominant modality of modern society. The problem with Ong’s theory wasn’t that he was wrong about the effects of writing; he was wrong to create a hierarchy between orality and literacy.

American psychologists Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole provide a critical refinement. In the 1970s, they tested the idea that “literacy makes you smarter” by studying the Vai people in Liberia . The Vai provided a unique opportunity because they used three completely separate literacies for different purposes: a local script for personal letters and business records, Arabic for reading and memorizing the Quran, and English for Western-style schooling.

If Ong were right, any kind of literacy should have produced a general cognitive boost. Instead, Scribner and Cole found the opposite. Each literacy only improved the skills tied to its actual use: the business writers got better at business writing, the Quranic students excelled at memorization, and so on. The only group that showed the kind of abstract, metacognitive growth Ong described were the students engaged in academic writing. Scribner and Cole thus clarified the “when” of productive struggle.

But what about the “how”? What is it about academic writing that builds metacognitive muscle?

David R. Olsen, a Canadian psychologist and literacy theorist, provides a compelling answer in his 1994 book, The World on Paper: The Conceptual and Cognitive Implications of Writing and Reading. Olsen argues that writing is not just a way to record speech but a technology that provides a model for language itself. This model allows us to analyze the structure, grammar, and precise meaning of words, separate from the speaker’s immediate intent, which is the foundation of metalinguistic awareness and abstract thought.

The “desirable difficulty” of writing, then, is not just in finding the words. It is the recursive, often agonizing, loop of:

Generation: Externalizing a half-formed, oral-style thought onto the page.

Inspection (Metacognition): Looking at that thought and asking: “Is this true? Is this clear? Does this logically follow?”

Revision (The Action): Clarifying, structuring, and rebuilding the thought because you saw its flaws.

These tentpoles of research are buoyed by hundreds (probably thousands) of studies underpinning the role of productive struggle in building the mind, and it brings us to the central challenge of this essay: what happens when a technology comes along that is designed, quite literally, to mimic this entire process?

Co-Writing with AI

A lot of people I speak with seem to think they have the answer: we simply need to let go of traditional conceptions about how people write, and encourage students to use AI as a tool that augments, rather than replaces, their own thinking.

Put another way, rather than struggle through the process of writing essays, in the near future students will struggle through the process of co-writing with AI, and we should aim to push them to employ sophisticated forms of prompt engineering that tap higher-order thinking and build metacognition.

This isn’t necessarily wrong. I agree with the premise that co-creation with AI is an inevitability, and students who are highly effective at harnessing AI will have an advantage, especially given the aggressive push in the corporate world for that skill set.

But even though AI literacy is extremely important to be ready for the future, I believe being proficient in effectively using AI tools is not a replacement for being proficient in traditional, old-school writing—by hand (or cursor), without the help of AI.

Part of that belief comes from the rich body of research from the learning sciences that I’ve detailed above, but I also worry that it’s really hard to ensure AI doesn’t make things too easy.

Consider the below prompts and outputs. Let me know your guess as to which goes with which:

Prompt A: “Hi make wright a gud profesh Graf bout y kids need gud to be at wrighting no halp from AI”

Prompt B: “Please draft four sentences explaining why it’s critical for students to develop writing skills without relying on AI to generate the first draft. It should address the importance of kids learning to express their own ideas, build confidence, critical thinking, and a genuine voice. Here’s some context that I’d like to include: I want to make the point that these skills don’t just help with completing essays or tests; these skills equip students for success after graduation—not just in college and in their careers, but in everyday life. I also want to say that writing from scratch is important for strengthening memory, helping kids truly understand what they are learning rather than just repeating information. Please use a professional tone for a general audience.”

+++

Output 1: “Developing writing skills without relying on AI to generate the first draft is essential for helping students learn to express their own ideas clearly and authentically. Writing from scratch strengthens memory and deepens understanding, allowing students to internalize what they learn rather than simply echo information. This process also builds confidence and critical thinking—skills that prepare young people not only for academic success but for effective communication and problem-solving throughout their lives. Ultimately, cultivating a genuine voice through independent writing empowers students to participate meaningfully in school, work, and everyday interactions.”

Output 2: “Strong writing skills are essential for every student because writing teaches clear thinking, creativity, and communication. When kids learn to express their own ideas in writing—without relying on AI—they build confidence, critical thinking, and a genuine voice. These skills don’t just help with essays or tests; they prepare students for success in college, careers, and everyday life. Writing from scratch also strengthens focus, memory, and problem-solving, helping kids truly understand what they’re learning rather than just repeating information. Developing writing skills gives students the ability to persuade, explain, and reflect—abilities that will remain valuable no matter how technology changes.”

Whether or not you got the answer right, it’s obvious why this poses a problem. There’s no way to reliably evaluate whether productive struggle is taking place by observing the output.

If the goal is assessing student understanding, teachers will be able to make use of adapted teaching strategies (projects, debates, presentations, etc.), but we also need to teach students to write. There is no substitute for putting pen to paper (or cursor to keyboard).

While this may seem like a contrarian take for a founder of a nonprofit called aiEDU, it’s actually the same advice that Maureen Heymans, VP of Engineering and GM, Learning at Google, shared on “Raising Kids”:

“When you use AI tools, it’s super important that you don’t offload too much of the cognitive exercise to those tools… you really want to empower your own thinking first. If you want to do some creative writing, start by writing the first draft before you go back to the AI. It’s important that we generate our own point of view.”

The results of my AI-generated Substack experiment

My readers will recall that my last Substack post was entirely AI-generated. I’m sorry about that. It’s cringy. But I did it for science! And I learned something valuable: the AI-generated post performed about the same as previous ones.

In fact, given the post has only been out for two weeks, it probably will end up being one of my best-performing posts.

Here’s what an AI-generated version of this Substack would look like. On the surface, it’s very well written. It’s shorter, has a consistent structure, and gets all of my main points across without going too long. I’ve spent about 10 hours working on this piece; the AI-generated one took me less than 5 minutes.

My response: I don’t care. Writing is a hill I will die on.

I don’t see the value of adding one more stream of regurgitated information to the deluge of content saturating us every second of every day. And why would anyone subscribe to an AI-generated newsletter? I’d be better off just sending a daily list of ideas, URLs, and a draft prompt so that you can generate a synthesis in your preferred format.

It’s also possible that an AI-generated Substack would underperform over time. While a recent study found that half of all content on the internet is now AI-generated, 86% of the articles that end up being ranked in Google Search are written by humans; AI-generated text tends to rank lower than human-written text. Over time, the homogeneity of AI content will further dilute their perceived value.

But the most important reason I put the time in to write is the same reason that kids need to put the time in to write. In the ten hours I’ve spent hacking my way through the research and drafts and re-writes, I’ve learned about the studies that explain what had previously been intuitions. I’m equipped with an interesting, perhaps even valuable, conversation topic. I’ll be able to draw on this in panels, roundtables, and myriad other settings with a depth that I could never achieve if I were just riffing off the initial idea that I had when I set out to write this post.

Because writing is thinking.

+++

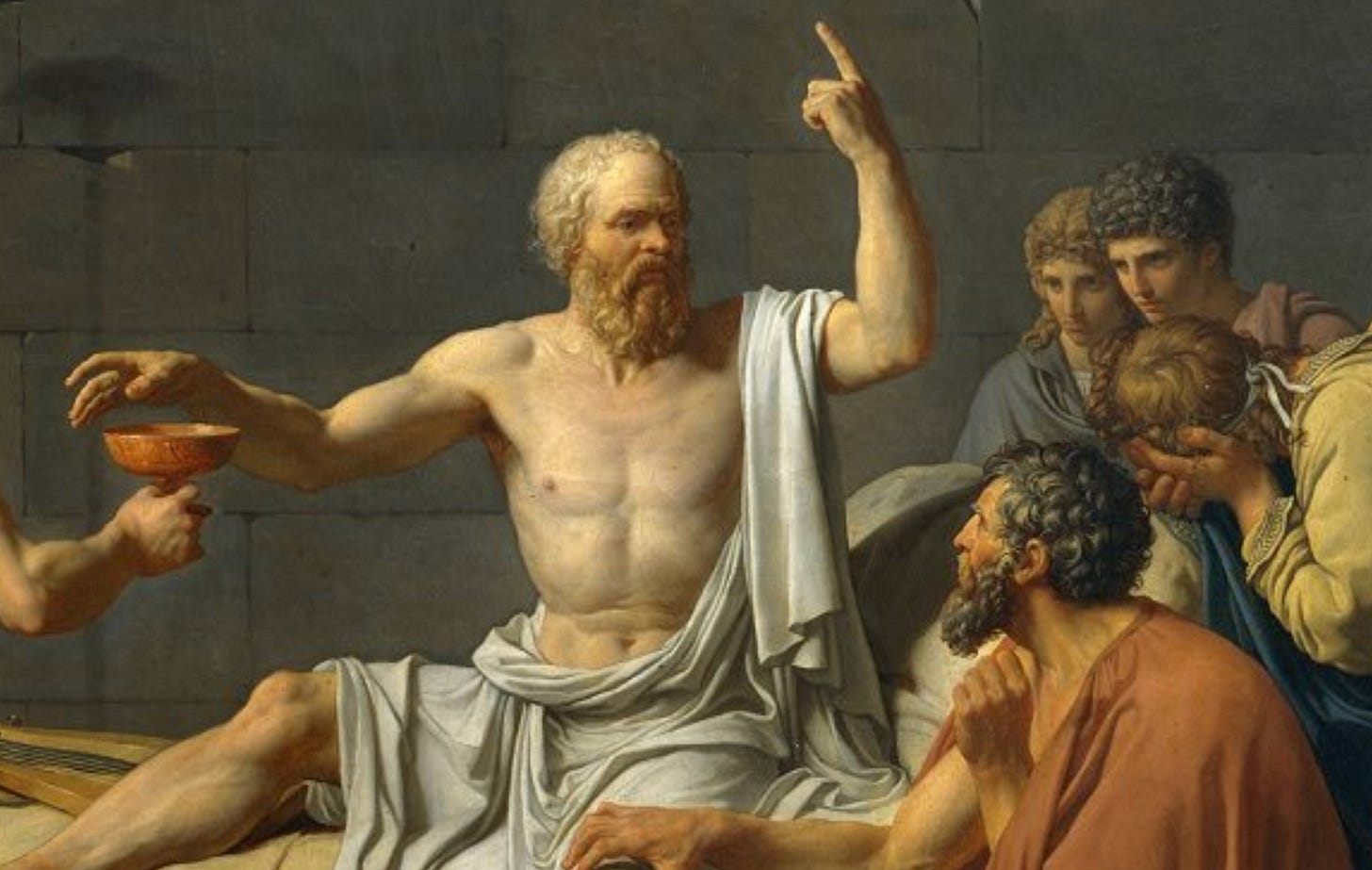

P.S. — The shrewd reader will note the irony of using an illustration of Socrates, a man who famously argued against the written word. He feared it would weaken our internal memory, and allow people to seem knowledgable without doing the hard work of thinking…

P.S.S. — While I’m an ardent proponent of the importance of writing not being replaced by AI, it’s also the case that I use AI extensively in my own writing process, primarily to conduct research. I originally had a section detailing that process, but it isn’t easy to describe and the section grew so long that I decided to save it for a future post. Stay tuned. And if you have a strong opinion about how to use AI for writing, please email me: alex@aiEDU.org

P.S.S.S. — I was a prolific user of the em dash and have been horrified at the fact that they are now seen as a “tell” that something has been AI-generated. There are a couple sentences in this piece that were written by AI, but none of them contain an em dash.

I thought about this quite a bit, but couldn’t figure out a way to truly A-B test. If anyone is aware of some studies that would showcase this please share!

And yes, I agree that it would have been more scientific not to indicate the prior post was written by AI, but I didn’t feel comfortable duping folks.

This is one of the best pieces I’ve read on sub stack in a long time… very well done exceptionally clear, and I had to share! Great job Alex!