The writing "doom loop"

AI is already generating half of the content on the web...

Preface: I wrote this post with my friend and colleague Nathan Kriha. Nathan works on policy for EdTrust, a national nonprofit that advocates for equity in public education. We spent a lot of time debating how to make the case for writing skills in the age of AI, and after a long phone call realized that we had an interesting take that would be worth… writing about. Nathan deserves credit not only for helping to write this piece, but for helping to shape my thinking overall about this topic and more.

+++

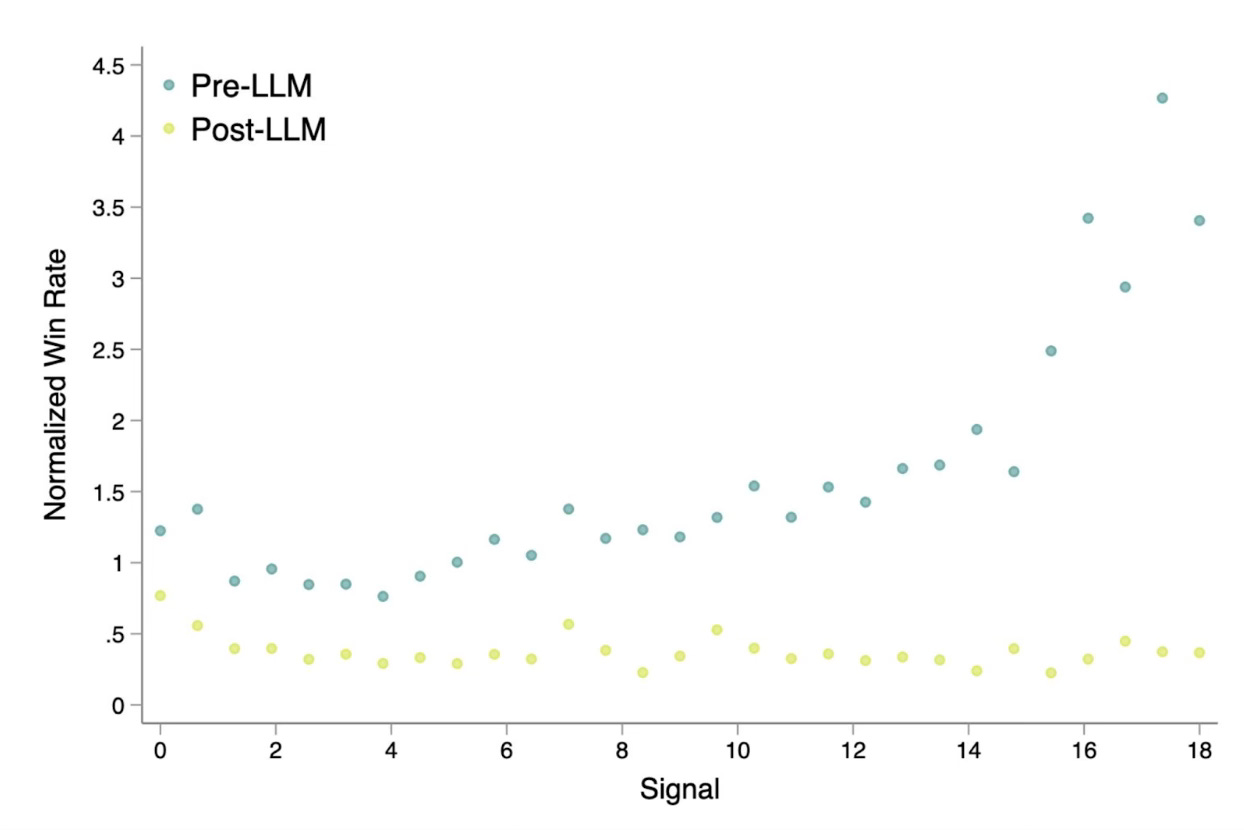

Economists Anaïs Galdin from Dartmouth and Jesse Silbert from Princeton tried to measure this in a paper titled Making Talk Cheap. They studied coding jobs on Freelancer.com, where workers apply with short written proposals. In April 2023, Freelancer.com rolled out a built-in AI tool that helps applicants auto-draft those proposals. Galdin and Silbert used an LLM to measure the degree to which each proposal is tailored to a given job, and got access to click-stream data to estimate how much effort went into writing it.

Before the AI tool went live, highly tailored proposals were harder to produce and strongly predictive of real ability and successful job completion, so employers were willing to “pay” for quality applications.

After widespread AI adoption, that correlation broke down. AI-assisted proposals look polished regardless of the applicants’ underlying skill, and thus lost their value as predictors of good work.

Galdin and Silbert used a structural model to simulate a world where written applications no longer signal anything about ability and find that the market becomes less meritocratic: workers in the top quintile are hired 19% less often, while those in the bottom quintile are hired 14% more often.

This study has been making waves because it explains a phenomenon that hiring managers have been talking about for a while now: a “hiring doom loop” where the escalating use of AI by job seekers is massively increasing the volume of applications. There’s also been an increase in the number of highly tailored resumes and cover letters. The result is a homogenization of candidates that appear more similar, making it difficult for managers to identify outstanding individuals.

It’s not the job-seeker’s fault. First, the vast majority of companies (88%) use AI-powered job screening tools, creating an arms race where all but the most exceptional candidates are forced to use AI to have any chance of getting through to a human review. Second, companies are explicitly seeking candidates with experience using AI. Over half of all job postings in 2024 required some AI competency, and the percentage is rising rapidly. Job posts explicitly requiring AI skills surged 73% from 2023 to 2024 and then another 109% from 2024 to 2025. If anything, it would be malpractice for candidates not to use AI. Hence the “doom loop.”

College application essays are likely on the way out as well. Duke University has already stopped giving essays numerical ratings in their undergraduate admissions process.

Other schools have responded by trying to use AI to solve the problem it is creating: UNC Chapel Hill, Virginia Tech, Texas A&M, and Georgia Tech are all integrating AI tools to review essays. This is folly.

It might take years of admissions cycles for what happened on Freelancer.com to play out, but make no mistake, that’s where we are heading.

Writing is under siege

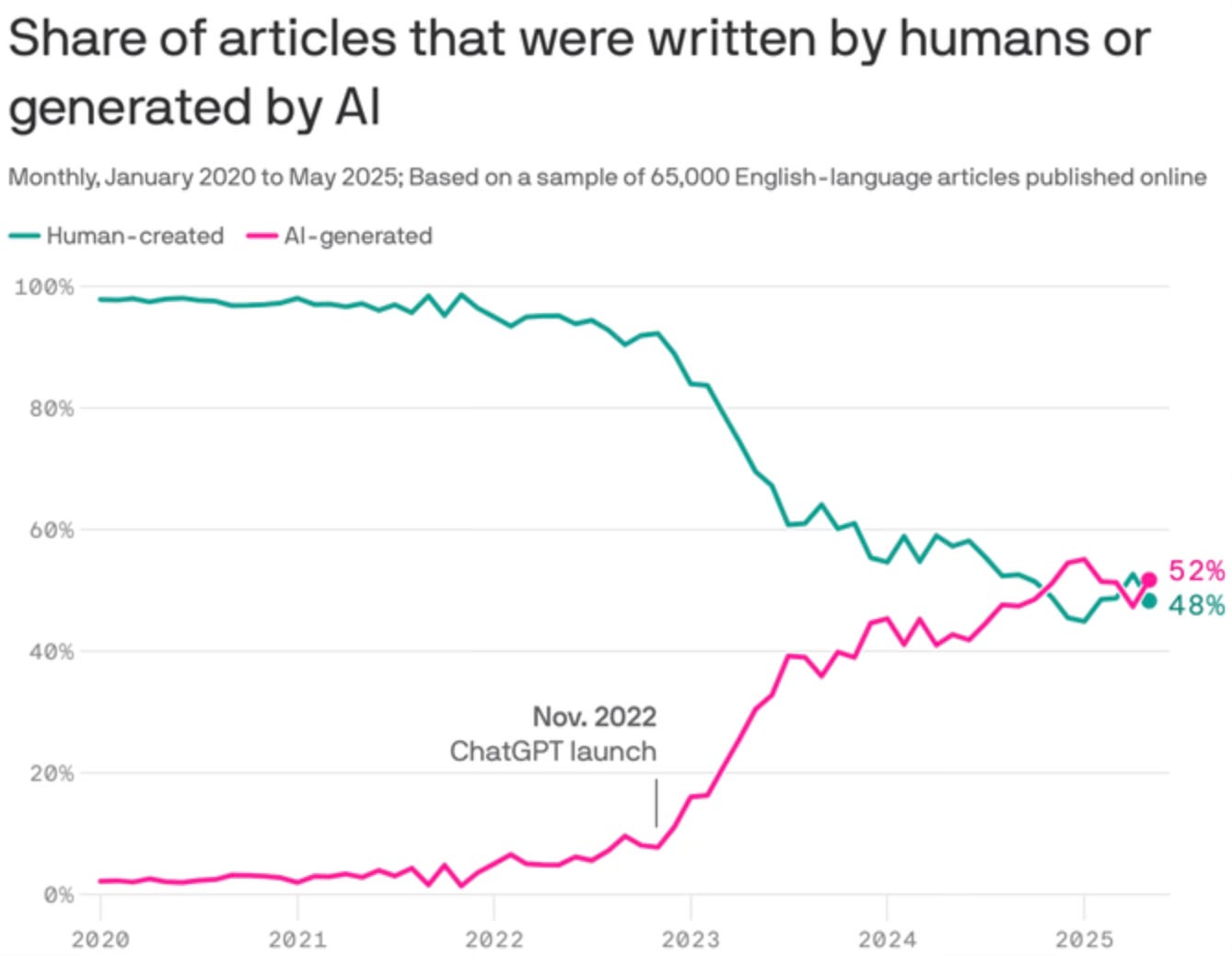

Overnight, AI-generated text has taken over the internet. Half of all text online is now AI-generated. That includes LinkedIn posts. Some of it is obvious, and some of it flies under our nose; in general, research has shown that humans can accurately identify AI-generated text about 50% of the time.

In economics there’s a concept called the “Market for Lemons.” Developed by George Akerlof in 1970, it describes how asymmetric information can destroy a market. This occurs when one party in a transaction (usually the seller) knows much more about the quality of a product than the other party (the buyer). In Akerlof’s classic example of used cars, sellers know if their car is a high-quality “peach” or a low-quality “lemon,” but buyers cannot easily tell the difference. Because buyers can’t be sure, they are only willing to pay an average price. This average price is too low for the owners of peaches, so they leave the market. As the good cars disappear, the average quality of the remaining cars drops, causing buyers to lower their prices even further, until only lemons are left.

It seems this is what’s taking place in the world of content. Writers (sellers) know how much effort, originality, and genuine thought they put into their work. However readers (buyers) can no longer reliably distinguish between high-effort human writing and cheap, AI-generated text. A logical reader would treat all content as potentially suspect, offering a discounted level of trust and engagement. Sooner or later, the perceived reward will no longer be enough to compensate the human writers for their effort, and they’ll lose the incentive to produce high-quality work. AI lemons will flood the market, driving out the human-written peaches, leading to an gradual but definite decline in the quality and trustworthiness of online content.

This is already coming true. Analysis by SEO firm Graphite found that AI-generated text now makes up about half of all the text on the web. The company pulled a random sample of URLs from Common Crawl, an 18-year open-source database containing over 300 billion web pages, and categorized articles as “AI-generated” if less than half of its text was deemed to be written by a human.

To be honest we’re surprised we’re only at 50%…

This radically changing, and inarguably worsening, era of the internet seems to be signaling a world where human-generated writing is valued less by consumers and, especially, the platforms that host and disseminate content. We are staring at a potential, maybe even likely, future where a “writer” uses AI to churn out some written work and the “reader” uses AI to summarize said product, all done in the name of efficiency. The text itself becomes nothing more than digital sludge, a token of communication passed between two machines that strips away most human-driven process. But it’s the very processes involved with writing — crafting arguments, piecing together narratives, researching the field, and building one’s understanding of the topic area — that help us become better learners and thinkers.

Remember, writing is thinking. The real problem we are trying to identify here is the growing reliance on generative AI may be facilitating the deterioration of people’s writing and learning journeys by decoupling text from thought — what we are calling the writing doom loop.

In K-12 and higher education contexts, preserving (and maybe even prioritizing) this link between writing and thinking will become critical as we settle into the AI era. We cannot allow widespread adoption of AI tools to smooth over the friction, the productive struggle, students encounter as they learn to write and critically analyze text — when a student outsources writing processes to AI in the spirit of efficiency, they are bypassing the work required to synthesize disparate ideas, challenge their own perspectives, and strengthen their critical thinking and analysis skills.

Beyond erosion of skills, there is a more profound risk to individual agency and the development of a student’s unique voice. Nathan here: During my undergraduate years, I had the honor to work at the University of Notre Dame’s Writing Center. All tutors, before even setting foot in the writing center to lead a session, had to hone their craft through a semester-long Writing Center Theory and Practice course. This class equipped us with various strategies for tutoring students on their written works — we learned how to ask probing questions as the primary vehicle for our feedback, methods for identifying incongruities and structural issues, and what it looks like to build an inclusive and welcoming environment for all learners. While that course and my years at the writing center undoubtedly made me a better writer, looking back, the most crucial lesson I learned wasn’t a specific technique but a simple truth: there is no right way to write.

This may feel overly obvious but the reality is that somewhere during our development as writers we discover our unique voice — the patterns, vocabulary, structures, and even beliefs that differentiate our writing style from others. My job as a writing tutor was to preserve that unique voice in every assignment on my desk which meant, first and foremost, refusing to offer specific language or edits for someone to simply co-opt; instead, I would have a conversation with an author to probe the rationale behind certain decisions, letting them come to their own conclusions about how to strengthen their piece. While there were surely ethical reasons for this rule — namely, to prevent students from treating the center as an essay rewriting service — I viewed it primarily as a pedagogical imperative: the process of writing, of putting pen-to-paper and grappling with language, was critical for the development of a learner’s voice.

It should be clear to everyone reading, but the educational purpose of writing is not often about producing technically correct answers — it’s about cultivating the confidence to wrestle with ambiguity, uncover and assert a viewpoint, and express oneself earnestly. When students skip the messy, nonlinear processes of writing they miss out on something deeply human: the opportunity to better formulate their thoughts and develop their voice. By prioritizing or allowing a frictionless pathway, we signal to students that the polished, algorithmically average outcome is as or more valuable than their own developing, imperfect, and uniquely human perspective. In essence, widespread utilization and reliance on AI for writing will teach students a dangerous precedent: there is a right way to write, and it’s however the premier LLM does it.

Let’s hope it doesn’t come to this.

This is the entire challenge right here: How do we keep the learning while using it alongside the tool?

Alex you make some great points here, but the one that truly stands out to me: remember to be the friction.

I'm not anti-AI. I spend much of my time working with it, and it extends my capabilities in ways I couldn't have imagined 5 years ago.

But I am staunchly pro-friction, because it's the *only* way we maintain our cognitive sovereignty.

I've been very torn in my own writing — figuring out how much to do "the old fashioned way" and how much to let AI build for me.

I often use AI to varying degrees, but always making sure the core ideas are mine. That said, the line where I call something "mine" has gotten very blurry — because in the process, I always gain some new perspectives I hadn't considered.

I still consider it a creative process, but one that requires a very different skillset from traditional writing.

If I had to label that, I'd call it "sparring" more than "writing".

I wrote this comment. No AI. And I left it messy, because there's something to be said for that too.

It's an act of subterfuge against my own perfectionism.

//Scott Ω∴∆∅